Amelia Nelson (284)

As November 8 marks National STEM day, it’s no secret that STEM continues to be one of the most male-dominated fields. According to the National Science Foundation, while the distribution of men and women in the labor force is almost even, the distribution of men and women in STEM workforces is a 70-30 split. Despite interest, factors like reinforced stereotypes, a lack of representation, and unconscious bias continually force women out of STEM fields as education level increases. Recently, the Cornell Chronicle suggested that high school, where most students begin their STEM journeys, may be one of the most influential times for helping women find and stay in STEM. So where does Central stand?

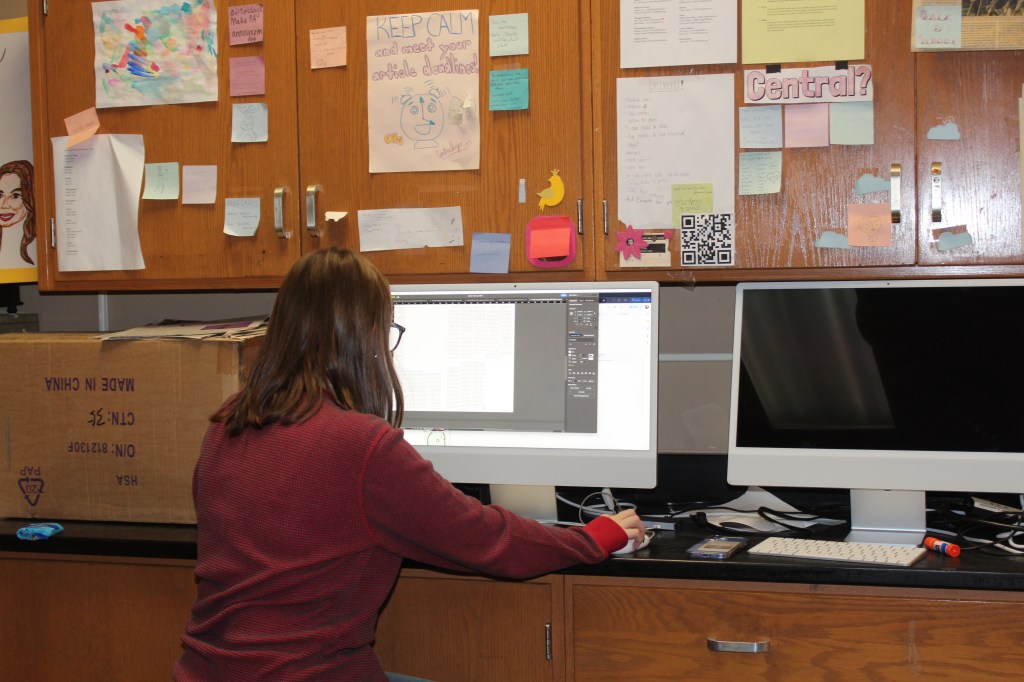

In a survey given to AP Computer Science, AP Physics, Engineering, and Robotics students, only 17 (29.8%) out of 57 responses were from female and non-binary students. While this isn’t an exact representation of all the gender splits in Central’s STEM classes, it’s a close estimate. Dr. Feofanov’s AP Physics C only has 8 girls (25%) out of 32 students, yet that’s a “record-high number” for the class. In some cases, this lack of other female peers discourages attendance, participation, and self-confidence. One 12th grader in Engineering shared that being “the only girl in her group” led to feelings of “disconnection” and that she “just wasn’t intellectually competent enough.” She added that she didn’t think their behavior was intentional, but “simply existing around them” when it’s “so natural to put girls to the side” was challenging.

A double standard for women to succeed can also contribute to a competitive environment. One 12th grader who has taken AP Physics 1, 2 and C, AP Chemistry, and AP Calculus AB and BC commented that even though Central has fostered her love of STEM and she plans to continue pursuing her studies, competition in male-dominated classes has often made her feel “dumb and naive.” She wishes she could experience STEM without constant comparison to her male peers. A different 12th grader in Engineering argued that because of that double standard, it felt “empowering to be doing as well as the boys.” Conversely, that also means that women performing worse than men in STEM is expected– it’s “girly” to fail.

Despite this, one Central STEM class presents as a major outlier: AP Biology. Completely opposing all other statistics, the class is over 70% female. Biology teacher Mr. Fitz incorporates teaching about STEM gender inequality in his classroom with the hope he can encourage conscious and stereotype-challenging students. One 12th grader said the female-dominated class was a “better environment” compared to her other STEM classes. Another noted that Biology was a refreshing chance to not feel intimidated in STEM. A majority of female students in the class simply responded that gender didn’t affect them. They could best thrive when additional pressure was removed.

This doesn’t mean that just having more women in STEM classes will completely bridge gaps, but it suggests that representation is one important factor. Girls Empowering Minds in STEM (GEMS) is, as vice president Alix Leon (284) says, an “opportunity to be a woman in STEM.” The Central club provides a welcoming space where women can explore fields of STEM without having to be scared of failure. By hosting STEM-related field trips and speaker panels, Alix hopes GEMS can educate the Central community on STEM inequality and provide role models and representation for women in STEM.

Part of the issue is a lack of awareness. One 10th grader described that she saw and experienced harmful gender gaps in STEM, “but not ways that were noticeable to the boys.” Many others responded that they wanted more direct education about issues and solutions. Changing a longstanding, male-dominated STEM culture is a hard task and gender is only one dividing factor. But Central is ready, and the benefits of a more inclusive STEM environment are definitely worth it.