By Juan-Lin Chow

Education is often considered the secure and traditional gateway to success, and in our current school system, the major determinant is a single letter grade. All the effort and thought we put into a class–– participation, study sessions, and after-school hours– is supposedly reflected in that singular evaluation. Over the past decades, general trends correlate to an increase of A’s that are given out to students. Data going as far back as the 1960s map out the growing percentage of students that receive high grades, and the numbers are still on the rise, suggesting an increase in grade inflation. Similar to real inflation, grade inflation is when students are given higher grades than earned, often yielding an overall higher average and raising the grade standards for that class.

The amount of A’s that current students receive is much higher compared to just a few decades ago. In fact, an article from the New York Times states that “most recently, about 43 percent of all letter grades given were A’s, an increase of 28 percentage points since 1960 and 12 percentage points since 1988.” However, at college-level institutions, the grade inflation crisis seems to be at its worst. During the post-pandemic year of 2021-2022 at Yale University, the percentage of students who obtained a grade in the general A range broke over eighty percent. Does this indicate a pattern of consistency that the students are putting in the hard work and commitment that an A entails? Not necessarily. If this was true, then the nationally-increasing GPA would be marked in positive correlation with some other measurable factor like national and state testing. Instead, the “average SAT scores fell from 1026 to 1002. ACT scores among the class of 2023 were the worst in over three decades.” How can grades be on the rise while other testing shows a contradicting result?

A reason for grade inflation could be the absence of effort on both sides. It is simply easier to assign a good grade. When a teacher gives a student an A, the student is satisfied and feels validated for their work, and the teacher does not have to deal with the constant waves of emails of complaints that they are all too familiar with. In this case, grade inflation is understandable. However, when everyone gets the same grade, the standards will drop while making it feel like the curtains of expectations are being slowly raised. If the majority of students are achieving A’s, then a student with a B will be the disparity. Grade inflation also has a lack of regard for the difficulty of the class —the difference between a regular or honors class, for example— because everyone inevitably gets high grades.

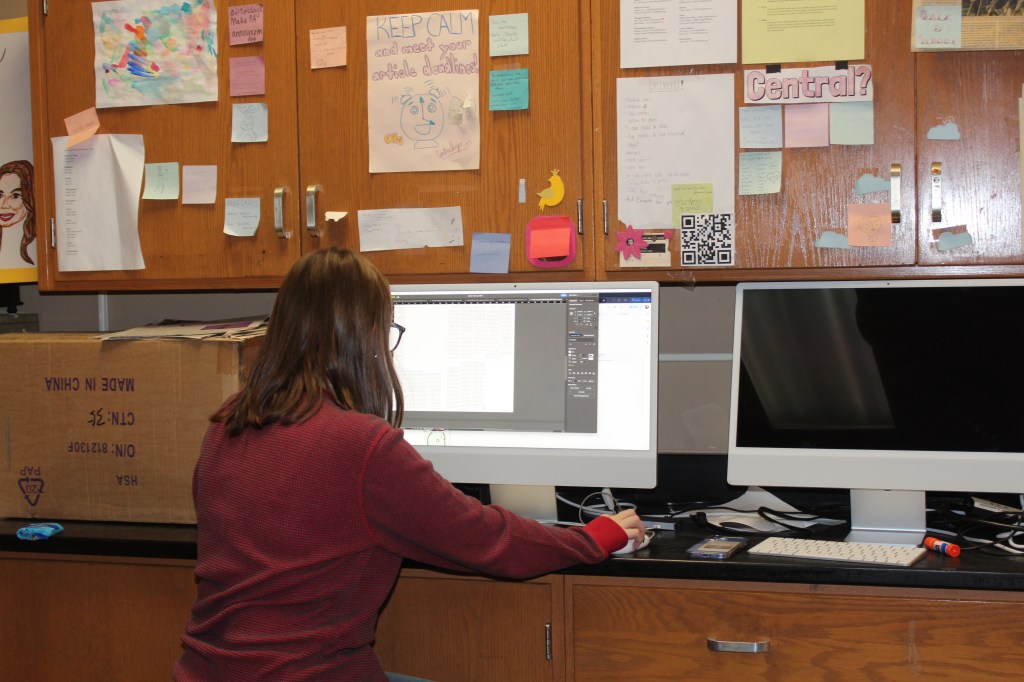

Ms. Brooks, an educator of twelve years and a current IB English teacher at Central, shares her experience with grade inflation. “During the pandemic and after, understandably so, there was such a focus on student emotional and mental health that academia took a backseat. A byproduct of that was grade inflation. Now, we’re at a place where things are getting back to normal, and I think that our grades need to be deflated again.” She highlights the pandemic as one of the causes for grade inflation during the recent years. When asked about the importance of grades, she emphasized the necessity in assigning students honest grades as it also helps them develop skills that can be used outside of the classroom by saying, “I think that students receiving B’s and C’s when it is earned, helps them develop resilience, self-awareness, and the power of reflection, thinking about the ways in which we can fall short, and in ways we can grow and improve. I think it’s really important for grades to accurately reflect student work.”

As the lines are blurred, it puts so much more pressure on those who seemingly lack behind, setting “A” as the expectation, when we’ve forgotten that it was the “B” that we were all striving for at the start.