Sadie Daniel (283)

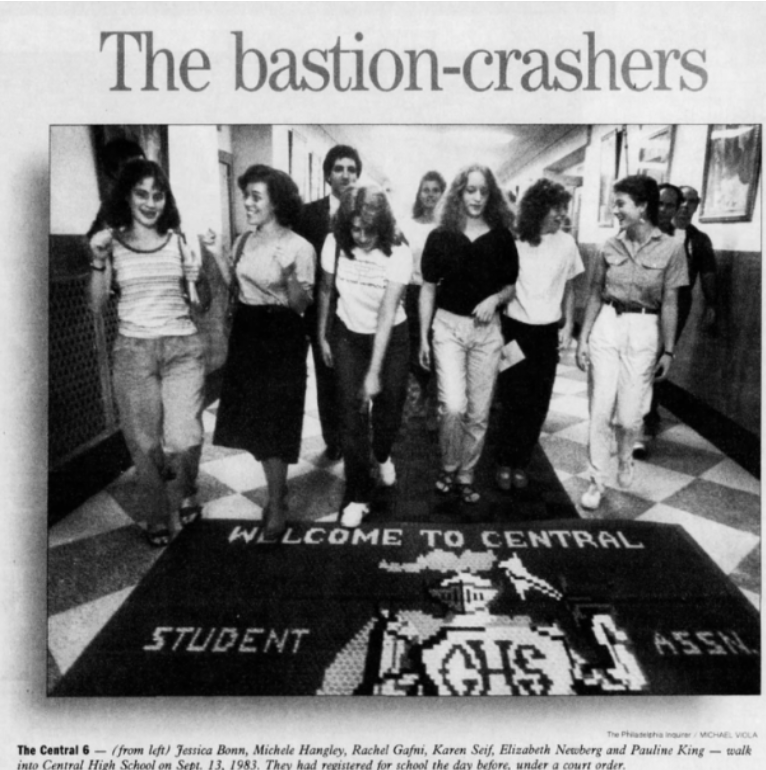

For 139 years, Central was an all-boys school and stood as the most prestigious high school in Philadelphia. Countless amazing stories and alumni came out of Central, excluding women. Twelve years after Central opened, the City of Philadelphia opened up the Philadelphia High School for Girls so that Central would have an “equivalent” counterpart. Yet, it was clear that for those 139 years, they were far from equal. Central had far more resources, making them unequal sister schools. Over the twentieth century, Central’s admissions requirements were challenged three times. One of which was in the early 1980s, when three female applicants sued the school district again under state law. These three girls, Elizabeth Newberg, Pauline King, and Jessica Born, claimed that Central’s admissions policy violated the equal rights amendment in the Pennsylvania Constitution. Thus, in 1983, the case was accepted by Judge William M. Marutani, who declared that the resources and opportunities at GHS were “materially unequal” to those at Central. In a 5-3 school board vote, his decision was passed, making Central co-educational.

However, the story feels quite surface-level without hearing the view of girls who lived through it all. A Baltimore City Schools art teacher, Mrs. Laura Emberson, who attended Girls High in the eighties, told the story of how the girls challenged the School District of Philadelphia to let girls into Central, and so for the fortieth anniversary of the 1983 decision to become co-ed, Mrs. Emberson was asked for her perspective on the story.

A majority of Girls High students opposed the change. Mrs. Emberson told me, “We didn’t like it because we knew it meant GHS would go down. GHS had the top ten-percent of girls in the city, so if some of them went to Central, we would get less than ten-percent,” and the girls challenging the court never surveyed GHS students. “GHS was always thought of as being less than Central,” said Mrs. Emberson.

Students of GHS didn’t feel like they lacked anything until the case began. “Suddenly, it felt like our classes weren’t good enough, even when we felt like they were perfectly good.” It was clear that Central had better classes, its teachers were more qualified, and speakers such as Noam Chomsky were rumored to have taught there. While the GHS students weren’t entirely in favor of the change, Mrs. Emberson’s high school best friend, Katherine Allen Adams (GHS 229), had another perspective: “That first year was more challenging than I ever could have imagined. They [the girls] were not seen as heroes in their entry into the student body at Central and were perceived as dissolving the sacred fraternity of masculinity. The girls were outsiders and constantly reminded that they did not belong.” According to Adams, while the GHS community was divided on this change, it “opened the eyes of many to what is possible when a value is the goal. The value of equality in excellence in education would go on to be a foundational block at Central.”

The Central Six changed a lot for Philadelphia high school students. It opened the opportunity to attend Central for girls across the city, finally allowing them to access classes and teachers they couldn’t have accessed at GHS. But it also damaged the stature of Girls High significantly, something Mrs. Emberson found to be “a shame” as these girls are no longer receiving the same quality of education. Central has gone to thrive within the co-ed atmosphere: when Mr. Horwits asked Coach what the best thing that ever happened to Central was, Coach, of course, said “Girls.”

Leave a comment